“Another Déjà Vu? Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) Gene Therapy Faces Setback”

“Another Déjà Vu? Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) Gene Therapy Faces Setback” In the final chapter of my 2012 book, The Forever Fix: Gene Therapy and the Boy Who Saved It, I made a prediction that gene therapy would revolutionize healthcare.

But, well, it seems I was a tad too optimistic. Fast forward to 2023, and we’re still grappling with the complexities of this groundbreaking technology. The gene therapy landscape isn’t quite the revolutionary health utopia I envisioned.

READ: Gossip Mill: Disney’s Fresh Flicks Set for Live-Action Remakes

DMD, Meet Jesse and the Viruses

You might remember Jesse Gelsinger, the poor fellow who ventured into the world of experimental gene therapy back in 1999. He had a rare disorder, and after receiving the treatment, he met an untimely demise. The culprit? Viruses going rogue and stirring up an immune ruckus.

Jump to 2023, and we’re reading about a young man with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) who passed away just days after his gene therapy. History, it seems, enjoys repeating itself. Jesse had a rare urea cycle disorder, and the viruses meant to deliver good genes turned rebellious, triggering a meltdown in his liver.

Gene Therapy: Still a Rarity

While a few lucky folks have had their vision saved thanks to Luxturna, the list of gene therapies approved by the FDA remains disappointingly short. High costs and limited patient responses haven’t helped either. It’s like playing the lottery but with more tears and fewer jackpots. We urgently need a better way to figure out who will benefit from these treatments.

Take Zolgensma, for instance. It’s approved to treat spinal muscular atrophy. Children affected by this condition don’t usually make it past infancy, so you can imagine the hope it brought. Videos of kids dancing post-treatment made us all smile, but there’s a flip side too. A recent case saw an infant treated with this $2.25 million gene therapy, and by the time he was eight months old, his most significant achievement was keeping his head up for a few seconds.

FDA has given the green light to six gene therapies, but they’re hidden in a list of 32 Approved Cellular and Gene Therapy Products. Now, let’s not get confused; the cell-based ones mainly target cancer. And there are some interesting additions, like a treatment for knee pain that involves growing cartilage cells on pig collagen. Oh, and they’re injecting 18 million of your own fibroblasts under the skin to fill out “nasolabial fold wrinkles.” Well, there’s a remedy for everything these days, it seems.

The approved gene therapies are for clotting disorders, retinal blindness, and the severe skin peeling condition, dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. The sixth one targets DMD but only in little boys aged 4 to 5 who can still walk. The warning label mentions adverse effects like liver trouble and heart inflammation, but it somehow forgot to mention lung damage, which, ironically, was the cause of our recent hero’s demise.

Big Genes, Little Hope

The 27-year-old DMD patient had inherited a massive mutation in a gene on the X chromosome from his mom. It’s the largest gene in the human genome, with a whopping 2.2 million DNA bases. This gene is responsible for producing dystrophin, a protein crucial for our muscles. When it goes wrong, as in DMD, it’s like a Jenga tower collapse – muscles crumble, and life gets tough.

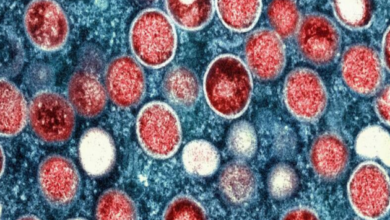

The DMD gene therapy delivers a truncated version of the dystrophin gene, just 4,558 DNA bases. Two key changes were made: adeno-associated virus (AAV) was called in to do the gene delivery instead of the adenovirus (AV), which had caused havoc in Jesse’s liver. And secondly, CRISPR gene editing was brought into play to fix the mutation. It’s like trying to patch up your favorite jeans instead of buying new ones. They call it “custom CRISPR-transactivator therapy,” which sounds fancier than it is. It’s all about editing a specific mutation and hoping to make enough cells work better.

The man’s own body gave a helping hand in this story. Certain brain neurons retained parts of the gene, so the researchers used CRISPR to nudge his muscle cells into producing a mini-version of the needed protein. It had worked in test tubes and even in mice. But reality is a tougher critic.

A Fast and Furious Decline

Our hero started the treatment on October 4, 2022, and things spiraled down faster than a runaway rollercoaster. Within a week, he went from experiencing a few premature heartbeats to a full-blown health rollercoaster.

By day 5, he was dealing with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and his heart was struggling. A day later, it was game over. The autopsy painted a grim picture, revealing obliterated air sacs in his lungs.

Immune Battle: Innate vs. Adaptive

So, what went wrong this time? Like Jesse, our DMD warrior didn’t have the luxury of time for the adaptive immune response to kick in. You see, your immune system has two layers of defense. The innate immune response is like the first responders, releasing general anti-viral agents. In this case, it went a bit haywire, leading to ARDS, all thanks to the super-powered gene therapy dose.

Autopsy revealed that the gene therapy concentrated in the lungs and liver but didn’t quite reach the muscles. There weren’t any antibodies against the virus used. So, it was the innate immune response, the ancient one, causing all the chaos. It flooded the heart and lungs with inflammatory proteins, and well, you can guess the rest.

Challenging Evolution

In a rather ironic twist, it seems that our age-old immune system might be the biggest challenge in our quest to tame the genes. The innate immune response, the ancient one that’s been with us for a billion years, is like the bouncer of the club – it’s tough to get past.

On the flip side, the adaptive immune response, which is relatively new, is more like the polite but overly cautious guest list checker. It only appeared around 450 million years ago and is exclusive to vertebrates.

In the end, it appears that, despite our fancy tools and tech, we’re still going up against a billion years of evolution. Perhaps, as we continue our quest to fix genes, we should remember that Mother Nature has been in the game for quite a while and isn’t giving up her secrets that easily.